Why craft work matters now more than ever

We’re at a moment in human history where the world’s ambition has finally outpaced our capacity to build.

Housing, energy systems, infrastructure, factories, AI compute, climate resilience, becoming multi-planetary and entire categories of physical systems we haven’t yet conceived of, are all being put in jeopardy by a shortage of skilled workers and the absence of systems to coordinate their skills across physical industries with speed, scale, and reliability.

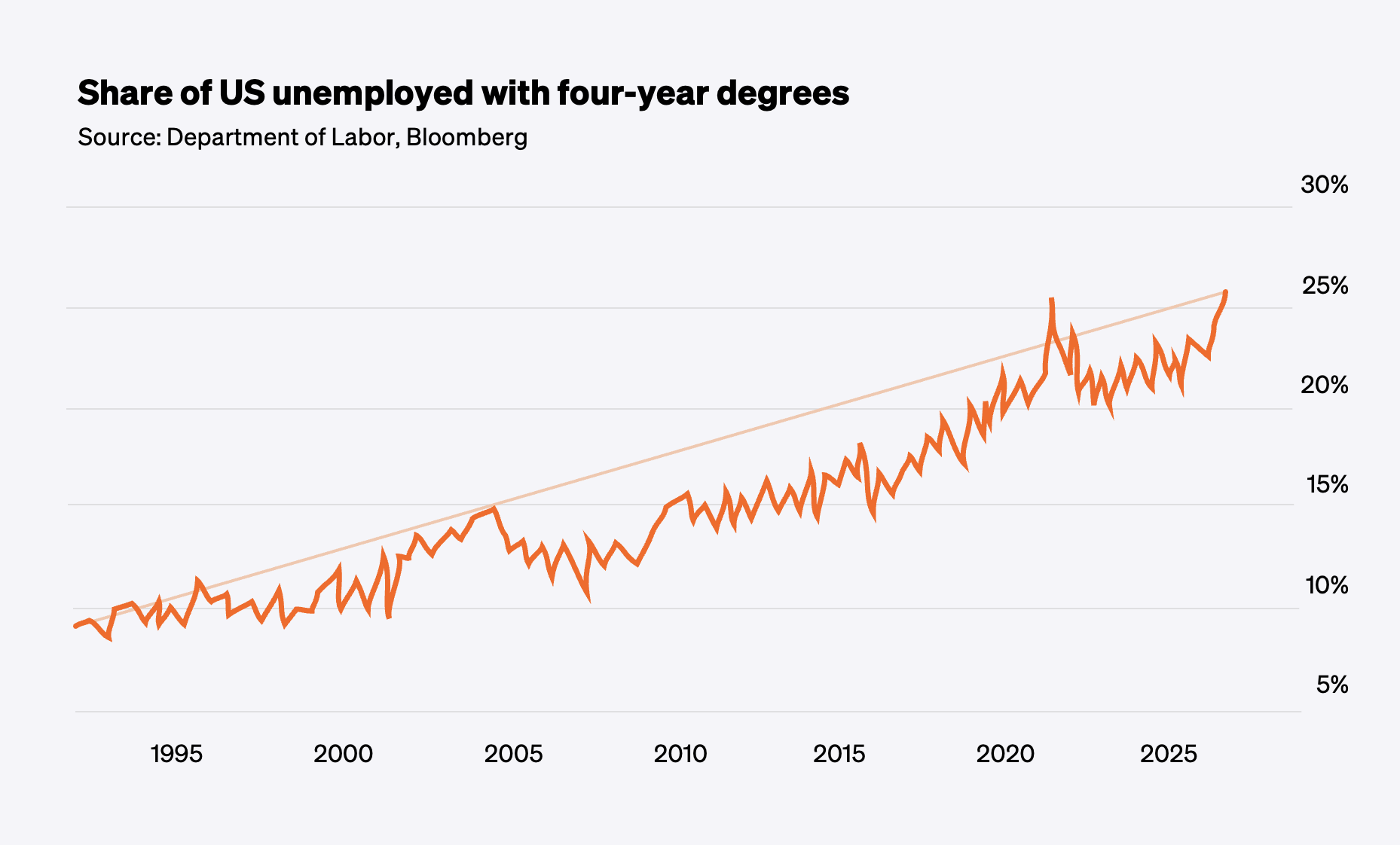

At the same time, a growing share of people are underemployed or stuck in fragile career paths. Over 25% of Americans with four-year college degrees are unemployed right now, the highest level ever recorded. That figure has been rising steadily for more than two decades and now affects nearly two million people over the age of 25. That’s not a cyclical blip but the result of a labor market that has become structurally misallocated.

How we got here

Beginning in the late 1950s (perhaps around the time Sputnik triggered a cultural and economic arms race? LinkedIn mostly agrees) America chose to transform its higher education system from “nice to have” into “oh shit, this is essential to America’s future!!!” Over time, Washington and Wall Street built an enrollment-driven financing machine (think loans, subsidies, incentives etc.) pushing generations toward knowledge work pathways regardless of whether the labor market actually needed them. Unfortunately, it didn’t, which is why it couldn’t fully absorb the high volume of graduates.

Meanwhile, vocational and craft pathways, particularly in construction, continued to offer stable, middle-class careers without massive debt, yet were systematically under-invested in, poorly coordinated, and hard to access. The result is underemployment on one side of the economy, and capacity constraints on the other, resulting in the creation of a civilizational-level choke point that must be solved if humanity is to achieve any of its lofty goals.

Now as we enter the era of AI, it’s becoming clear that not all work is equally resilient. Knowledge work, especially entry-level, abstract, low-consequence work, is being rapidly compressed and industrialized by AI. Meanwhile, physically embodied skilled work, the kind performed by roughly one billion people globally to build and maintain the real world, is surging in demand and proving far more resistant to automation.

The implication is of course very clear: the world must transition millions of people into these roles over the coming decades if we are to keep building at the pace our ambitions demand and keep our economies healthy. That is Skillit’s mission: to scale the world’s craft, so that anything can be built, anywhere. If we’re going to solve this problem honestly however, there are two common objections that need to be addressed:

People don’t want to do physical work anymore!

Well, according the data, they do. Every year in the U.S. alone, nearly 500,000 people attempt to enter construction through apprenticeships, trade schools, CTE programs, helpers, and entry-level roles. The problem is that fewer than ~40% persist long enough to become economically productive because the early path is so fragile. From unstable hours and volatile earnings to upfront costs and poor placements, once this system fails them, it rarely brings them back. This isn’t a motivation problem. It’s an access, routing, and conversion problem and it’s fixable.

Robots are just going to do it all anyway.

I first heard this claim about 30 years ago from an academic telling me I should quit being a carpenter. It underestimates the nature of craft work and the reality of deploying robots.

Humans didn’t become the dominant species on Earth because we’re the strongest, fastest, or even the smartest. We evolved outrunning prey over long distances thanks to thermal regulation (not the point of this post but the animal would topple over from heat exhaustion and we’d spear them) and the ability to carry heavy loads (i.e. said prey) over terrain back to camp. Running and carrying. Endurance and strength. That's the foundation of the human operating system and craft work engages that full stack: mind, body, judgment, dexterity, stamina and real-world risk and accountability. That’s what craft work is and it is a devilishly difficult thing to automate, let alone make socially and economically viable and risk-tolerable to employers.

The timelines are also laughably optimistic. Take autonomous vehicles (a far more constrained and repeatable problem than construction), they’ve been in development for over 20 years but despite trillions in investment, they represent only ~1% of miles driven. Construction is orders of magnitude harder - dynamic environments, unstructured terrain, safety-critical interactions, reliability thresholds north of 99.9%, tight feedback loops, integration with legacy systems, human co-presence. Yes, humanoid robotics research is advancing rapidly, but the gap between what works in a demo and what works on a real jobsite is vast.

Also, even if automation improves productivity, it doesn’t remove the constraint. In supply-constrained physical systems, efficiency gains tend to unlock more demand because things get cheaper and faster to build (see Jevons paradox), and so societies choose to build more which increases the need for skilled people who can plan, supervise, integrate, and work - even alongside machines.

Scaling the world’s craft

Despite having nearly one billion people performing physically embodied skilled work across construction, manufacturing, energy, utilities, logistics, and other physical industries today, it won’t be enough to meet the demand ahead. Global investment in the built world is accelerating across every dimension from housing, energy transition, infrastructure, advanced manufacturing, and AI compute and adding tens of trillions of dollars of incremental physical build over the next two decades, with construction alone projected to grow by more than $10 trillion globally. Meeting that demand will require millions more skilled people working alongside increasingly sophisticated tools and machines — coordinated at a level of speed, reliability, and scale today’s labor systems were never designed to support. This is not simply a labor shortage. It’s an infrastructure gap.

If we want a society that can keep building and progressing, we need a new kind of AI-powered labor infrastructure, that’s what Skillit exists to build, and it starts by fixing access to craft labor.